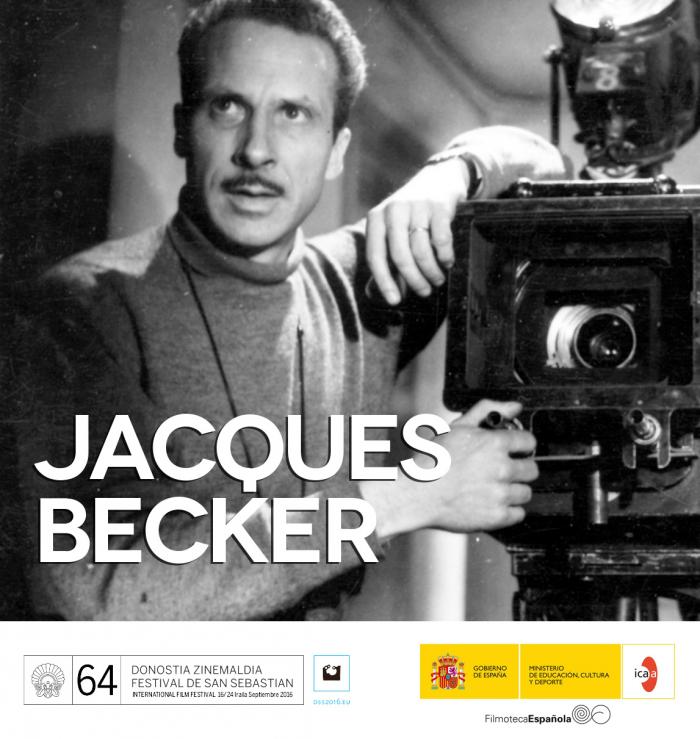

The 64th edition of the San Sebastian Film Festival will dedicate a retrospective to the French director Jacques Becker

The 64th edition of the San Sebastian Film Festival will dedicate a retrospective to the French director Jacques Becker

|

Jacques Becker, who was born and died in Paris (1906-1960), only made thirteen feature films in a relatively short period of time, between 1942 and 1960. However this baggage small in number but prolific in important titles such as Casque d’Or (Golden Helmet, 1952), Touchez pas au grisbi (Hands Off the Loot, 1954) and Le Trou (The Hole, 1960) was more than enough to earn Becker consideration as one of the essential names of the evolution of French cinema.

Communist in his beliefs, although he never made social cinema in the strict sense of the word, Becker trained in the cinema of the Popular Front and worked as an assistant to Jean Renoir. His influences came both from the work of the author of La grande illusion (Grand Illusion, 1937), one of the eight films by Renoir on which Becker worked as an assistant, and from the classic North American movies made prior to World War II. He was a huge fan of King Vidor and Howard Hawks, for example. His style stemmed from a sort of classicism, soon moving into modernity, refining itself at neck-breaking speed during the occupation and post-war period. It comes as no surprise that the majority of the influential Cahiers du cinéma critics always defended him as being one of the few directors saved from the generalised attack on French post-war cinema: for Truffaut, Godard and company, enemies of academicism, Becker was always on a par with his mentor Renoir, with Jean Cocteau, Jean-Pierre Melville, Max Ophüls, Robert Bresson and Jacques Tati.

A lover of detail and meticulous both when recreating periods in the studio or shooting outdoors, stylist of the mise-en-scène and creator of unrepeatable atmospheres such as the romantic and violent Casque d’Or (Golden Helmet), Becker practiced impressionism and realism equally, paying as much attention to the historical periods of his tales as he did to the psychology of his characters. The Cahiers du cinéma critics saw in him the modernity that they themselves would put into practice on moving into production as part of the Nouvelle vague. His early days were anything but easy. Prior to his official debut with Dernier atout (1942), Becker made a couple of shorts, participated in a collective documentary promoted by the French Communist Party on the Popular Front electoral campaign – La vie est à nous (1936), with the collaboration of Jean Renoir and Henri Cartier-Bresson, among others – and began the shooting of L’or du Cristobal (Cristobal’s Gold, 1940), finished by Jean Stelli and for which Becker never felt responsible.

While the spectator will find all kinds of different genres in his cinema, none of his films fully correspond to the codes of a specific category, despite being based on notions as obvious as comedy – Antoine etAntoinette (Antoine and Antoinette, 1947), Rendez-vous de juillet (Rendezvous in July, 1949), Édouard et Caroline (Edward and Caroline 1951); melodramas with Goupi mains rouges (1943), Falbalas (Paris Frills, 1945), Rue de l’Estrapade (1953); gangster movies with Touchez pas au grisbi, an exceptional detective story with Jean Gabin and Casque d’Or (Golden Helmet), a fabulous portrayal of the Paris underworld in the early 20th century, with Simone Signoret and Serge Reggiani; the artistic biopic Montparnasse 19 (The Lovers of Montparnasse, 1958), a peculiar look at the last two years in the life of painter Amedeo Modigliani and the tale of a prison escape to which he gave, with Le Trou (The Hole), what was perhaps the masterpiece of the genre. One of the strongest characteristics of his style is the reinvention of codes and formats. He also made movies of more popular roots with a film of exotic adventures starring Fernandel, Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs (Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, 1954), and another of mystery and sophisticated white-gloved thieves, Les aventures d’Arsène Lupin (The Adventures of Arsène Lupin, 1957).

Becker died on 21st February 1960, a month before the French premiere of his posthumous work, Le Trou (The Hole). His remains rest in Montparnasse cemetery. He had two sons, the filmmaker Jean Becker and the director of photography Étienne Becker, who died in 1995. In the last years of his life, Jacques Becker was married to the actress Françoise Fabian.

The retrospective, including all of Becker’s feature films, half of which were never commercially released in Spain, is organised by the San Sebastian Festival in collaboration with the Spanish Film Archive. To complete the season, a book will be published about the director, coordinated by Quim Casas.